Exhibitions

Below you will find photo reports from some of the exhibitions of Martina Czech's work

2023 - 2024

The Flying Paintress

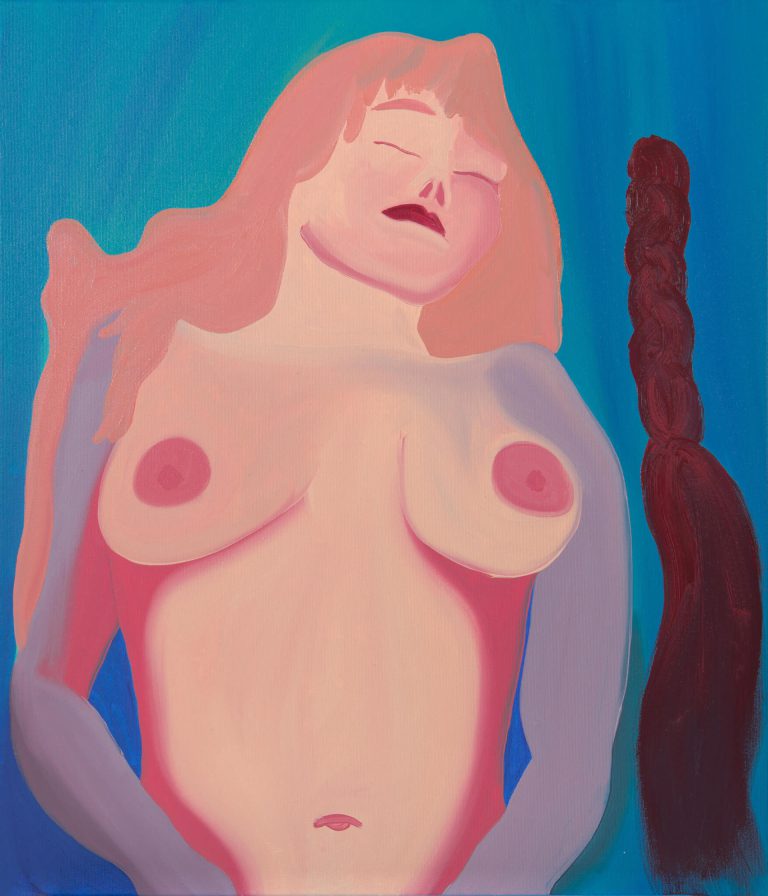

Both content and form find blunt expressiveness in these paintings

Expression is her element

The flying paintress

Conveys content linked to her manner of being

With her style of putting a spanner in the works

The form of this painting is in line with the themes of the

Aggressive distortion of the figure, sometimes doused with the sauciness of obscenity

Astonishing color combinations

Astute choices regarding composition

Paintings refined thanks to their cruel simplicity are remembered

These paintings are ablaze

Never is it boring or lukewarm

Intensity is one hundred percent guaranteed

Challenging the worn out forms of painting culture

The painting gathers momentum like a crazed locomotive and speeds to its destination

The painter touches the dark sides of existence

At other times, she toys with black humor

She finds meaning in painting the obscene

Over the last few years, a personal style of painting has been clarifying

There is a lot of rebellion here that gives the impetus to act

It is essential that it produces vital paintings

When the years pass, the same force of the paintings will always remain

Torn from the current personal and cultural contexts

The majority of significant things are determined outside the individual, as if in the shadows, as if in the unconscious

There is a lot of intuition here, the important thing is to be able to surrender to it and flow on

The gift of putting everything on a single page most often serves painterly expression

Provocative themes contribute to calling attention to the one who has chosen this path

Dramatic sets of shapes and colors in the end create an undeniable texture of the

It is worth striving for the goal that is beyond ourselves

Curator: Ryszard Grzyb

Expression is her element

The flying paintress

Conveys content linked to her manner of being

With her style of putting a spanner in the works

The form of this painting is in line with the themes of the

Aggressive distortion of the figure, sometimes doused with the sauciness of obscenity

Astonishing color combinations

Astute choices regarding composition

Paintings refined thanks to their cruel simplicity are remembered

These paintings are ablaze

Never is it boring or lukewarm

Intensity is one hundred percent guaranteed

Challenging the worn out forms of painting culture

The painting gathers momentum like a crazed locomotive and speeds to its destination

The painter touches the dark sides of existence

At other times, she toys with black humor

She finds meaning in painting the obscene

Over the last few years, a personal style of painting has been clarifying

There is a lot of rebellion here that gives the impetus to act

It is essential that it produces vital paintings

When the years pass, the same force of the paintings will always remain

Torn from the current personal and cultural contexts

The majority of significant things are determined outside the individual, as if in the shadows, as if in the unconscious

There is a lot of intuition here, the important thing is to be able to surrender to it and flow on

The gift of putting everything on a single page most often serves painterly expression

Provocative themes contribute to calling attention to the one who has chosen this path

Dramatic sets of shapes and colors in the end create an undeniable texture of the

It is worth striving for the goal that is beyond ourselves

Curator: Ryszard Grzyb

A brief cry of a small death, murmured within the four walls of the skull, the room and its world, but it's still too biological, too weak - like exhibiting and feeling emotions. Momentary cries of sadness, fear, strength, perseverance - brief orgasms of life, manifestations of normalcy, everyday life and a sign that the world continues to copulate over time. They saw in her a Ma-donna, an exceptional lady: small, big, old, young, fragile, persistent, and for one, she was everything. She fell from the pedestal to below the surface, and did all the flying monkeys looked on in awe at this great little fall? The monkeys had previously jealously watched her from below, but now with grinning muzzles, looking down, straight into her eyes, they clapped loudly. When this one daffodil withered, like other exceptional flowers in the past, they were gathered into a bouquet of tassels, love ended again. A replay of the past and everything for someone became nothing. A nail was driven into her heart, directly and mercilessly. Blood flowed thickly from the tender place, like smeared, dysentery lipstick of a fame-fatale. The price of being strong, perfect, desirable, and beautiful every day and every night, when inside loneliness plays the melody of apathy on the ribs. She became a cold she-fridgerator because how many times can one be the whiteness of the canvas when the greatest human gift to others: trust, is shattered a hundred times, and hundreds of drops of blood fall on this innocence? But nonetheless, the indestructi-belle rises from her knees, from the filthy floor, and stares them down hard right into their skulls: the flying monkeys, the daffodils, because she knows that it is not her time for eternal slumber in the dark graveyard of metal corpses. She must be strong, determined, and like a light shell, like a well-oiled machine, rise up and go forward, though those eyes are just waiting... she must be a seagull, which survives everything and finds herself everywhere... but lonely, and all she is able to make is a silent scream of strength melted into a cube of burnout. That's how every day, gathering burnt scrambled eggs from the floor, she laughs at them all and at herself, because black humor saves her life, which is like shittiness with scrambled eggs: it's just a mix of pre-made salads of irony, humor, and sarcasm. The paintress returns to those childhood times, but not the innocence, when grandma's slice of bread with butter and sugar was the only allowed sweetness. She remembers that joy when one bite was like a flight to heaven among clouds, birds, and, back then, doing nothing – just being oneself was enough to stand on the pedestal of love. She thinks about what happened, that she became the only child of her life, how did it come to this? Since she was so brave, courageous, determined, and stubborn, then why did this happen? Misfortunes never come singly, said the anxious monkeys, and a succession of daffodils, gazing into her eyes, reflecting their sickly images. No one told her that the sometimes bitter benzo-pills turn fate into hell; a real avalanche of bad shit, and no one advised on how to swim in this cesspool. She learned this herself, despite the inundation, where the internal battle for every breath of life cost more blood, tears, and sweat than the human norm predicted. Crawling out of it each time, she ripped the skin and flesh covering from her hands. The only friend of the paintress was stress, a daily companion, which verbally communicated to her what to do. She bit the meat off her fingers so hard that they turned red forever. Bit by bit, she faded from this world. The dysentery of being, a disease of the soul? Nothing could be further from the truth, it's an ordinary thing and a consequence of constantly pushing the limits. Such a gray existence without flair, to return to the pedestal one day, but the paintress learned from her mistakes and concluded that she would never touch the throne of love again. It was once at the top of her Maslow's pyramid, but it became an unnecessary illusion. Never again will she fall into the traps of naivety, helplessness, and subordination to the will of a withered stem, whose bud has long gone limp. More than once she caught a great eye, seemingly warm, good, emanating love, but it always turned out to be a frigid sheet of darkness. With each blink, she recoiled tighter and tighter into the depths of herself, sealing off her very being. She was lost in the pupil of promises, missing the flying monkeys and red lanterns of tired fingers. Only the eye mattered. The more she gave, the less she had left, but she knew how to swim, so she floated and drowned alternately in the darkness, bearing more and so on endlessly. The little I-lid cast the shadow of a big wolf, but she was devoured by another predator in the art of survival food chain. It was the mythical man. When she fell out from under his eyelid, she finally saw the truth: the omnivores were dismembering her slowly. She didn't know how to make herself whole, to put the puzzle of herself together, so she just sat dead in the chair. In the end, only she and the whiteness of the canvas remain.

The subject of the countryside, the bane of high school days, has recently returned with several high-profile publications settling accounts of our noble-Sarmatian historiosophy. "Boorishness" by Kacper Poblocki or "People's History of Poland" by Adam Leszczynski show us what each of us subconsciously knew; we are all from the countryside, we just mask it better or worse or repress it more effectively. Maybe that's why Martyna Czech's art seems so close.

What should art "about the countryside" be like? Peasant-oriented? Critical and stereotypical like from the famous film "Arizona" from the 1990s? Or perhaps like from the shelf in Cepelia; colorful, happy, kitschy? Is it possible to paint a hen, a bunch of strawberries or a country cottage without smelling tacky? "So what," says Czech with his latest series of works on paper. If you want to experience the countryside, put on your rubber boots, and hang your prejudices on a peg for a while. Twenty-odd works created in his native village in the Kielce region and juxtaposed together in the exhibition "Born from the village, by blood from the city" do not fit into any patterns. The countryside, like all other subjects of the works, interests Martina from the beginning, to the end, and not piecemeal. Life in her art begins with conception (in her case, it would be more appropriate to say copulation/banging/moving) and ends with the excretion and decomposition of organic substances. When I first saw these works, I imagined the painter standing behind a table and using a butcher's cleaver to chop meat into pieces. Each sliced slice is a fragment of the living, fleshy, bloody entity that is the Polish countryside. One slice is beautiful and nutritious, another stringy, overgrown with fat or downright rotten.

„Rodem ze wsi, krwią z miasta” brzmi jak tekst z tatuażu. Martyna nigdy nie lubiła zbędnych słów. Ma być krótko i na temat. Bardzo często tytuły jej prac to zbitki słowne, tworzone jakby po to, by tytuł nie zajmował zbyt wiele miejsca („Choryskop” „Gołodupka”, „NiemaMoc”). Fraza „Rodem ze wsi, krwią z miasta”, jak kilka prac na wystawie, balansuje niebezpiecznie na granicy kiczu. Kto nie widział Martyny wypowiadającej te słowa z bezwzględną pewnością siebie, ten nigdy do końca nie zrozumie ich siły. Czech nie pokazuje swoich prac po to, by z nią polemizować albo się o nie spierać. Jest tak, a nie inaczej. Nie podoba się? Tam są drzwi!

Significantly, most of the works were created during her first extended stay in the countryside, where Martyna spent vacations as a child and where she was already "going for beans" as a teenager. Her "Bronowice" very often returns in paintings (portrait of her beloved, recently deceased grandfather, images of animal companions of childhood). This time Bohemia went there for a plein air painting (she herself would probably never call it that). Her status has radically changed; after all, she is no longer the same "Martynka," "cousin," but an established artist who is covered in the newspapers, and her painting costs as much as she would earn in a year working on beans. Has this changed her attitude in any way? In general. After all, she may be from the city by blood, but she comes from the countryside.

Curator: Michał Suchora

What should art "about the countryside" be like? Peasant-oriented? Critical and stereotypical like from the famous film "Arizona" from the 1990s? Or perhaps like from the shelf in Cepelia; colorful, happy, kitschy? Is it possible to paint a hen, a bunch of strawberries or a country cottage without smelling tacky? "So what," says Czech with his latest series of works on paper. If you want to experience the countryside, put on your rubber boots, and hang your prejudices on a peg for a while. Twenty-odd works created in his native village in the Kielce region and juxtaposed together in the exhibition "Born from the village, by blood from the city" do not fit into any patterns. The countryside, like all other subjects of the works, interests Martina from the beginning, to the end, and not piecemeal. Life in her art begins with conception (in her case, it would be more appropriate to say copulation/banging/moving) and ends with the excretion and decomposition of organic substances. When I first saw these works, I imagined the painter standing behind a table and using a butcher's cleaver to chop meat into pieces. Each sliced slice is a fragment of the living, fleshy, bloody entity that is the Polish countryside. One slice is beautiful and nutritious, another stringy, overgrown with fat or downright rotten.

„Rodem ze wsi, krwią z miasta” brzmi jak tekst z tatuażu. Martyna nigdy nie lubiła zbędnych słów. Ma być krótko i na temat. Bardzo często tytuły jej prac to zbitki słowne, tworzone jakby po to, by tytuł nie zajmował zbyt wiele miejsca („Choryskop” „Gołodupka”, „NiemaMoc”). Fraza „Rodem ze wsi, krwią z miasta”, jak kilka prac na wystawie, balansuje niebezpiecznie na granicy kiczu. Kto nie widział Martyny wypowiadającej te słowa z bezwzględną pewnością siebie, ten nigdy do końca nie zrozumie ich siły. Czech nie pokazuje swoich prac po to, by z nią polemizować albo się o nie spierać. Jest tak, a nie inaczej. Nie podoba się? Tam są drzwi!

Significantly, most of the works were created during her first extended stay in the countryside, where Martyna spent vacations as a child and where she was already "going for beans" as a teenager. Her "Bronowice" very often returns in paintings (portrait of her beloved, recently deceased grandfather, images of animal companions of childhood). This time Bohemia went there for a plein air painting (she herself would probably never call it that). Her status has radically changed; after all, she is no longer the same "Martynka," "cousin," but an established artist who is covered in the newspapers, and her painting costs as much as she would earn in a year working on beans. Has this changed her attitude in any way? In general. After all, she may be from the city by blood, but she comes from the countryside.

Curator: Michał Suchora

30.11 - 3.12.2022

NADA Miami

2021

Choryskop, Galeria Konkluzja, Hotel Dada w Krakowie

In the painting we see a peaceful, sleeping figure whose hair is arranged in the shape of a scorpion. Unaware, it is about to swallow its own tail, in which venom is hidden. Doesn't the personification of the scorpion, then, become the uroboros, the mythical snake that eats its own tail and is reborn from itself?

Horoscopes were put up as early as in ancient times. The names of the zodiac signs are derived from the names of the constellations given to them by the Sumerians 3-4 thousand years ago. Around 500 BC, the Babylonians divided the ecliptic into 12 equal, 30-degree parts, which formed the zodiac, measured by a circle staggered by the Earth's motion around the sun. In the tradition of Polish painting, Janina Kraupe-Swiderska was famous for her interest in astrology, and horoscopes became a permanent part of her paintings.

Martyna Czech treats horoscope with a pinch of salt. Not interested in "magical" predictions of the future, she focuses more on its psychological aspects.

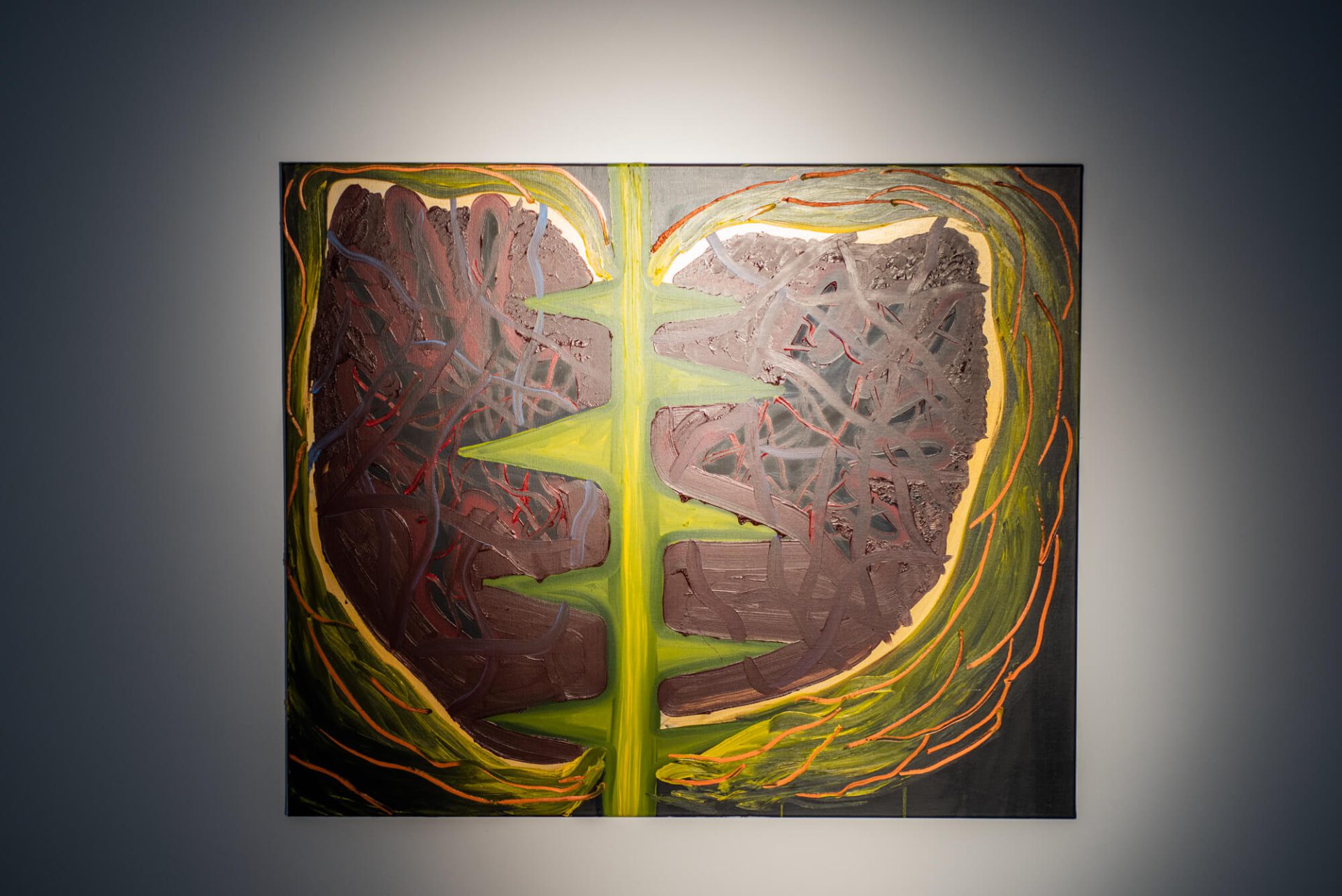

The artist, through her works, puts a painterly horoscope. A sick horoscope. After all, each sign of the zodiac has its vices, but tamed by the brush of Bohemia, who, sometimes painting intimate, erotic-saturated frames ("Aquarius", "Virgo", "Capricorn"), at other times showing only fragments of the human body such as the brain, heart , mouth ("Taurus", "Twins", "Libra"), brilliantly plays with convention, does not judge, allowing the final resolution of the meaning of the whole to the viewer. There is no shortage of animals beloved in the painter's world, and so swans become "Libra", "Lion" charms with its straightforwardness, and looking at "Cancer" we can see not only a woman's womb. When I ask about the painting "Virgo," Martyna muses, then replies: "When I was painting this picture, I thought about how much suffering modern man must carry on his shoulders."

Each painting has its own distinct story. After all, there is also a self-portrait of the artist ("Sagittarius"), suspended in a vacuum, stabbed by a man with love arrows from which blood oozes. The bow tightens, and in a moment another arrow flashes. Fragility. Undoubtedly Bohemia is a painter of emotions. An intelligent observer of timeless truths: spirituality and materiality, duration and transience, life and death - dependencies, seasoned at times with a pinch of self-ironic, black humor.

Curator: Renata Kluza

Horoscopes were put up as early as in ancient times. The names of the zodiac signs are derived from the names of the constellations given to them by the Sumerians 3-4 thousand years ago. Around 500 BC, the Babylonians divided the ecliptic into 12 equal, 30-degree parts, which formed the zodiac, measured by a circle staggered by the Earth's motion around the sun. In the tradition of Polish painting, Janina Kraupe-Swiderska was famous for her interest in astrology, and horoscopes became a permanent part of her paintings.

Martyna Czech treats horoscope with a pinch of salt. Not interested in "magical" predictions of the future, she focuses more on its psychological aspects.

The artist, through her works, puts a painterly horoscope. A sick horoscope. After all, each sign of the zodiac has its vices, but tamed by the brush of Bohemia, who, sometimes painting intimate, erotic-saturated frames ("Aquarius", "Virgo", "Capricorn"), at other times showing only fragments of the human body such as the brain, heart , mouth ("Taurus", "Twins", "Libra"), brilliantly plays with convention, does not judge, allowing the final resolution of the meaning of the whole to the viewer. There is no shortage of animals beloved in the painter's world, and so swans become "Libra", "Lion" charms with its straightforwardness, and looking at "Cancer" we can see not only a woman's womb. When I ask about the painting "Virgo," Martyna muses, then replies: "When I was painting this picture, I thought about how much suffering modern man must carry on his shoulders."

Each painting has its own distinct story. After all, there is also a self-portrait of the artist ("Sagittarius"), suspended in a vacuum, stabbed by a man with love arrows from which blood oozes. The bow tightens, and in a moment another arrow flashes. Fragility. Undoubtedly Bohemia is a painter of emotions. An intelligent observer of timeless truths: spirituality and materiality, duration and transience, life and death - dependencies, seasoned at times with a pinch of self-ironic, black humor.

Curator: Renata Kluza

2020

Martyna Czech. Evokes emotions, Clay, Warszawa.

Critics compare her art to the expressions of the 1980s, and also point to the painter's misanthropy. For example, for Martina Czech, humanity is just a herd of insects burrowing in shit. Someone else wrote that paint is yet another bodily secretion in Czech, as Czech paints her painterly cardiogram with venom.

The distinctive, expressive paintings are autobiographical: I'm interested in life itself, especially mine - because that's what I know. Each is an intimate story, a passage of experienced emotions. If taken seriously - rather in truculent, pale shades, if ironically - in vivid colors. Color is grating, unsettling. It builds up the painting: expressive, let go of detail. The canvases are created quickly: in one sitting, sometimes for hours - after all, the next day the artist might not feel the same way about a given story.

Simple compositions, tightly framed scenes are most often blunt, even violent. Sometimes obscene. She is interested in extreme states and feelings, violent behavior based on domination, submission and resistance to social relations so dissected. She observes, sometimes ridicules. Also herself. She is in it. He doesn't moralize. He works on the basis of the experienced. Things and states that cannot be forgotten. Toward people she is merciless. Animals sometimes from real heroes of her life, become allegories. It is sharp, brazen and bright. There are magnetic guts.

The painting, like ectoplasm, becomes an attempt to communicate. Painting, Bohemia makes use of the fuel of difficult emotions. The heavy subject matter of the canvas is light in a decisive painterly gesture reduced to a single brushstroke, sometimes to a flat stain, when a rough, fleshy impasto is needed. Sometimes the contrast, even bursts the sub-painting. The paint thinks along with Martina, feels along with the painter, understands her. Although painting is a medium for the eye, the body of paint here is always haptic, carrying or bearing the additional weight of meaning imposed by the representation. Guided by her brush, the matter renders the otherwise inexpressible. It transports not so much into the world of imagination - mostly close representations, in close-up, too close, voyeuristically assembled fragments of absorbed everyday life - as into the world of sensation. Martyna Czech's paintings are traces of operations on the living tissue of feeling.

Piotr Bazylko

I remember the moment when I saw the results of the 2015 Bielska Autumn, which was won by Martyna Czech. "Who is that?" - I asked myself. It was an absolute novelty for me. And yet Martyna had won the Grand Prix at one of the most important painting competitions in Poland. But when I looked at the prize-winning paintings, I knew I had to learn more about this artist. The paintings were different from everyone else: disturbing, inviting and repulsive at the same time. Simply interesting.

I started looking for information about Martina and saw that she was still studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice. I also discovered her Facebook profile. Thanks to this, I looked at all her work so far and this proved to be a breakthrough. I contacted Martina, took a long time to choose, but finally decided. In early 2016, on a cold, gray day, Martina brought me 5 paintings wrapped in an old comforter cover to Warsaw. I also remember our first conversation, because Martyna said she would finally have money for a decent stretcher bar. This completely captured me and I already knew that my choice was a good one.

This is how my adventure with Martina's paintings began, which surprises me all the time. It makes me say to myself time and again that I've had enough, that after all I don't have anywhere to hang her paintings anyway, and then I see another interesting painting by Martina and I put that resolve aside... until the next painting. Let me add right away that this is not an easy painting - some paintings directly exude bad energy, others are so intense that they can't stand any "company". And yet, as a collector, I can't help myself and just continue to collect more works by Martina Czech.

What fascinates me about Martina's painting? Its authenticity. In the age of Instagram's "everything for show," the enormous artificiality of what we show on the outside, the authenticity of her painting is downright overpowering. All emotions - good and bad - mix on the surface of the canvas and come out of the painting space. Martina paints what she experiences without using any anesthesia to do so. It's as if she doesn't use filters to anesthetize her emotions and thoughts for others, because they will offend someone, hurt someone or expose our true self.

In her paintings there is love and hate, suffering and joy, anger and sadness, ugliness and beauty of life. There are heroes of her life - people, of course, but especially animals: rabbits, aquarium fish, cows or cats. Finally, there is Martina herself. She titled one of her paintings Born of Paint. The painting is full of attributes of death and passing, and there is also a person resembling Martina. Naked, with her hands tied above her head. What does Martina want to tell us? That painting is suffering for her on the one hand, and necessity on the other? That she has no choice - she simply has to paint, in order to live? Because... she is Born of paint?

Tomasz Pasiek

I was very reluctant to meet Martyna Czech. I like meeting artists, especially in their studios, but I tried to avoid Martyna at all costs. Knowing her works, I expected the worst from this meeting. I felt that knowing her works, I already knew her myself. It turned out that the legend is close to reality. Sweet, but gutsy. But that came later. Much later. Before that it was worse. That Bielska Autumn and that first award. Noooo!!! A brush in your eye, juror! It's not painting, but Disembowelment (of paint, not of love). Troubled Girl, Shattered Millions of Pieces and her scribbles. Pussy imaginations. Ladies and gentlemen, here is my Selfie.

Painters-friends, like me, sniffed her from a distance, we were like a pack of mutts. It smelled bad to us, very bad. Just what it was, painted in a minute. But intoxicated we sniffed further. Painting hounds. I looked at it several times. And again. A dog's craving... No. Not worth anything. But I kept looking. IntereSik? Art? No, it's Zbuk. The complete impotence of art. My first painting I bought on a trial basis, a bit without conviction. And I fell in. Where did the Butterflies in the Belly come from? I really don't know how it happened that today Piotr Bazylko and I are showing her first solo exhibition in Warsaw, so full. Looking is addictive. Non-winding-ness. Amore mi potwore.

Ps. In the text, the words in italics are the titles of works by Martina Czech. Thank you.

The exhibition is organized as part of Clay.Warsaw's ongoing Clay.Art project, which promotes recent and contemporary art, as well as its collecting. Clay.Warsaw is a creative space that is a combination of a versatile studio, headquarters for production agencies, an interesting film location, an inspiring meeting and discussion place for the creative industry, and the organization of exhibitions and cultural events.

The distinctive, expressive paintings are autobiographical: I'm interested in life itself, especially mine - because that's what I know. Each is an intimate story, a passage of experienced emotions. If taken seriously - rather in truculent, pale shades, if ironically - in vivid colors. Color is grating, unsettling. It builds up the painting: expressive, let go of detail. The canvases are created quickly: in one sitting, sometimes for hours - after all, the next day the artist might not feel the same way about a given story.

Simple compositions, tightly framed scenes are most often blunt, even violent. Sometimes obscene. She is interested in extreme states and feelings, violent behavior based on domination, submission and resistance to social relations so dissected. She observes, sometimes ridicules. Also herself. She is in it. He doesn't moralize. He works on the basis of the experienced. Things and states that cannot be forgotten. Toward people she is merciless. Animals sometimes from real heroes of her life, become allegories. It is sharp, brazen and bright. There are magnetic guts.

The painting, like ectoplasm, becomes an attempt to communicate. Painting, Bohemia makes use of the fuel of difficult emotions. The heavy subject matter of the canvas is light in a decisive painterly gesture reduced to a single brushstroke, sometimes to a flat stain, when a rough, fleshy impasto is needed. Sometimes the contrast, even bursts the sub-painting. The paint thinks along with Martina, feels along with the painter, understands her. Although painting is a medium for the eye, the body of paint here is always haptic, carrying or bearing the additional weight of meaning imposed by the representation. Guided by her brush, the matter renders the otherwise inexpressible. It transports not so much into the world of imagination - mostly close representations, in close-up, too close, voyeuristically assembled fragments of absorbed everyday life - as into the world of sensation. Martyna Czech's paintings are traces of operations on the living tissue of feeling.

Piotr Bazylko

I remember the moment when I saw the results of the 2015 Bielska Autumn, which was won by Martyna Czech. "Who is that?" - I asked myself. It was an absolute novelty for me. And yet Martyna had won the Grand Prix at one of the most important painting competitions in Poland. But when I looked at the prize-winning paintings, I knew I had to learn more about this artist. The paintings were different from everyone else: disturbing, inviting and repulsive at the same time. Simply interesting.

I started looking for information about Martina and saw that she was still studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice. I also discovered her Facebook profile. Thanks to this, I looked at all her work so far and this proved to be a breakthrough. I contacted Martina, took a long time to choose, but finally decided. In early 2016, on a cold, gray day, Martina brought me 5 paintings wrapped in an old comforter cover to Warsaw. I also remember our first conversation, because Martyna said she would finally have money for a decent stretcher bar. This completely captured me and I already knew that my choice was a good one.

This is how my adventure with Martina's paintings began, which surprises me all the time. It makes me say to myself time and again that I've had enough, that after all I don't have anywhere to hang her paintings anyway, and then I see another interesting painting by Martina and I put that resolve aside... until the next painting. Let me add right away that this is not an easy painting - some paintings directly exude bad energy, others are so intense that they can't stand any "company". And yet, as a collector, I can't help myself and just continue to collect more works by Martina Czech.

What fascinates me about Martina's painting? Its authenticity. In the age of Instagram's "everything for show," the enormous artificiality of what we show on the outside, the authenticity of her painting is downright overpowering. All emotions - good and bad - mix on the surface of the canvas and come out of the painting space. Martina paints what she experiences without using any anesthesia to do so. It's as if she doesn't use filters to anesthetize her emotions and thoughts for others, because they will offend someone, hurt someone or expose our true self.

In her paintings there is love and hate, suffering and joy, anger and sadness, ugliness and beauty of life. There are heroes of her life - people, of course, but especially animals: rabbits, aquarium fish, cows or cats. Finally, there is Martina herself. She titled one of her paintings Born of Paint. The painting is full of attributes of death and passing, and there is also a person resembling Martina. Naked, with her hands tied above her head. What does Martina want to tell us? That painting is suffering for her on the one hand, and necessity on the other? That she has no choice - she simply has to paint, in order to live? Because... she is Born of paint?

Tomasz Pasiek

I was very reluctant to meet Martyna Czech. I like meeting artists, especially in their studios, but I tried to avoid Martyna at all costs. Knowing her works, I expected the worst from this meeting. I felt that knowing her works, I already knew her myself. It turned out that the legend is close to reality. Sweet, but gutsy. But that came later. Much later. Before that it was worse. That Bielska Autumn and that first award. Noooo!!! A brush in your eye, juror! It's not painting, but Disembowelment (of paint, not of love). Troubled Girl, Shattered Millions of Pieces and her scribbles. Pussy imaginations. Ladies and gentlemen, here is my Selfie.

Painters-friends, like me, sniffed her from a distance, we were like a pack of mutts. It smelled bad to us, very bad. Just what it was, painted in a minute. But intoxicated we sniffed further. Painting hounds. I looked at it several times. And again. A dog's craving... No. Not worth anything. But I kept looking. IntereSik? Art? No, it's Zbuk. The complete impotence of art. My first painting I bought on a trial basis, a bit without conviction. And I fell in. Where did the Butterflies in the Belly come from? I really don't know how it happened that today Piotr Bazylko and I are showing her first solo exhibition in Warsaw, so full. Looking is addictive. Non-winding-ness. Amore mi potwore.

Ps. In the text, the words in italics are the titles of works by Martina Czech. Thank you.

The exhibition is organized as part of Clay.Warsaw's ongoing Clay.Art project, which promotes recent and contemporary art, as well as its collecting. Clay.Warsaw is a creative space that is a combination of a versatile studio, headquarters for production agencies, an interesting film location, an inspiring meeting and discussion place for the creative industry, and the organization of exhibitions and cultural events.

4 July - 28 August 2020

Summoning, CCA Kronika, Bytom

For this touching act of sacrifice, the Emperor saves him from self-immolation, rewards him with immortality and sends him to the moon as an example for all mankind. This symbolic association of the rabbit with nobility, the simultaneous vulnerability of the species and the gruesomeness of the situation are reflected in the work of Martina Czech, for whom concern for the rabbit's fate is a kind of opus magnum. The artist's painting studio is at the same time a sanctuary for lagomorphs rescued from death, which find a special place in her paintings.

The animal element in the painterly visions of M. Czech also appears as a contestation of anthropocentrism - people are rather beasts, debased by their physiology and desire, whose punishment is inflicted by fauna, which is an emanation of universal morality. In this dehumanization of the characters, the artist's aversion to the human species, its abominations and formlessness is revealed. This aversion is continued in the abject animal material. Evoking death and the mystical totem of the rabbit made of accumulated matter in the form of bone glue, Bohemia proclaims the fatality of the entire collection. Humanity, as its greatest enemy, deserves not respect, but possession and loss of humanity. The secret mischief is accomplished through a reversal of order - a symbolic moment of pollution at the entrance to one of the exhibition rooms. Through the aesthetics of disgust, the artist directs our attention to the finitude of the subject, its inevitable disintegration and psychological hopelessness.

Paweł Wątroba

The animal element in the painterly visions of M. Czech also appears as a contestation of anthropocentrism - people are rather beasts, debased by their physiology and desire, whose punishment is inflicted by fauna, which is an emanation of universal morality. In this dehumanization of the characters, the artist's aversion to the human species, its abominations and formlessness is revealed. This aversion is continued in the abject animal material. Evoking death and the mystical totem of the rabbit made of accumulated matter in the form of bone glue, Bohemia proclaims the fatality of the entire collection. Humanity, as its greatest enemy, deserves not respect, but possession and loss of humanity. The secret mischief is accomplished through a reversal of order - a symbolic moment of pollution at the entrance to one of the exhibition rooms. Through the aesthetics of disgust, the artist directs our attention to the finitude of the subject, its inevitable disintegration and psychological hopelessness.

Paweł Wątroba

2019

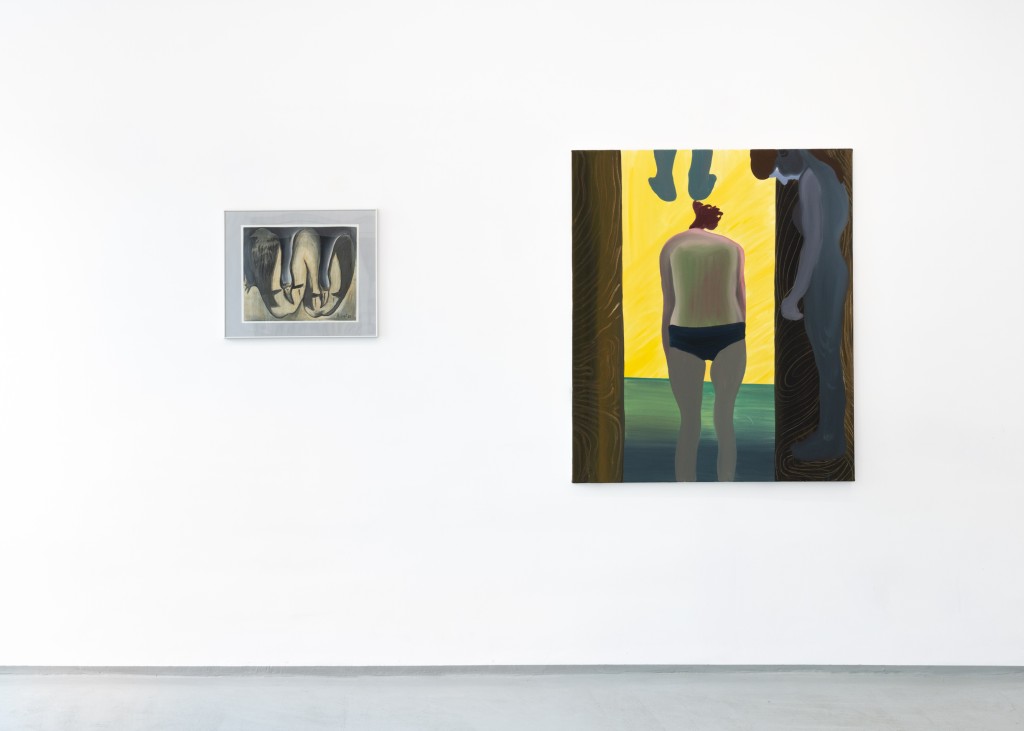

We have nothing in common, BWA Warszawa, Warsaw

It's hard to imagine two Polish artists more dissimilar to each other. Leszek Knaflewski was born in the midst of communist Poland, Martyna Czech in the first months of the Third Republic. He grew up in the bourgeois city of Poznań in a block of large concrete slabs, she associates her childhood with visits to her family in the Malopolska countryside. He experimented with all possible media except painting, she insists on using the traditional oil technique. His political views are not hard to guess, she "doesn't give a damn about politics." As if that weren't enough, Bohemian, unlike many artists of her generation, "doesn't jive with Knaf," whom she only began to discover in earnest while working on a joint exhibition. And yet, looking at the early works (those created shortly after college) of both artists, one can't help feeling that they share some kind of bond that is difficult to explain.

The animal motive? The first clue quickly turns out to lead to a dead end. In Knaf's early works there appear, among others, a horse, a cat, swans, but they are only a form, as important (or perhaps as unimportant ) as any other element. Leszek Knaflewski simply did not like animals. He didn't have them as a child, and as an adult he only paid attention to them in his works. The first animal appeared late at the request of his several-year-old daughter. It was a black cat named by her Knafi.

Martyna Czech grew up in a family with agricultural traditions. As a child, she spent a lot of time with her family in the countryside near Tarnow, so from a young age she had contact with farm animals. Importantly, this experience led her to treat them subjectively, rather than as livestock meant to provide their owners with milk, eggs and meat. This empathy was not blunted when she moved out to study, first in Cracow, then in Katowice. All the time the painter endured animals that fell victim to human predation in successive apartments. Animals in her paintings are often their main characters, treated with equal attentiveness to humans.

The differences in the representation of animals can also be seen on a purely formal level. Cats and pigs in Knaflewski's works are only contours, linear outlines, pictograms, graphic representations of some general concept. They are often preparatory sketches for large-scale installations signed "Circle of Clips." In Czech's paintings, the animals, most often her beloved rabbits, always have an individual feature, are more portrait-like, "full". In addition, the titles she gives them ("Subbush of the Crested Rabbit") refer to specific creatures or show a world of complicated emotional relations ("Revenge", "Devotion").

Symbolism? Knaflewski's early drawings and the sculptures and installations created from them are called examples of magic realism by art historians. The random-looking juxtapositions of objects had no rational explanation. These "beautiful as accidental meetings of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table" were the result of the artist's dreams and uncontrolled streams of thought. "Like an ironing board that was burned through with an iron and started surfing like a surfer on a wave," Knaflewski said of his object shown at the fourth exhibition of Circle of Clips at the Great 19 Gallery in 1995.

Any attempts to give them the marks of closed symbolic systems are dismissed by Ewa Moroń (Knaflewski's first wife), who witnessed the creation of the works for 20 years, with a smile. "Why a man with a house instead of a head? Because he does!"

Czech's paintings have a similar mental automatism and a complete lack of calculation. The motif of her painting can be anything: a rabbit, a mood, a word or phrase heard somewhere. Generalizing, Czech paints her immediate environment; the physical one, and the mental one. The artist always gives her works very specific titles, as if she doesn't want to let the viewer arbitrarily interpret her paintings. It's supposed to be this way and that. Sometimes they are brutally direct ("Painting Fowls," "Patch under the Nose"), at other times they are deliberately clumsily poetic ("Born of Paint," "Nostalgia of an Angel"). Anyone can think whatever they like about Knaf's works, Czech leaves no room for interpretation.

Lack of grand narratives? Knaf's drawings, shown at the exhibition, were created during an extremely intense political and social time. The turn of the 1980s and 1990s in Poland was the moment of the final collapse of the People's Republic of Poland and the new order, which was born in pain. This situation was bluntly commented on by the artists of Gruppa, Neue Bieremiennost or Luxus. The Klips Circle, of which Leszek Knaflewski was a member (alongside Mariusz Kruk, Krzysztof Markowski and Wojciech Kujawski), stood by. The draconity of declining communist Poland prompted them not to fight the system, but to build a hermetic, parallel world outside society and politics. They preferred metaphor to manifesto, poetry to politics.

Martyna Czech, in addition to the fact that she "doesn't give a damn about politics," despises attempts to interpret her work through the prism of any philosophical currents. Looking at her works, any solid academic begins to recall in his mind the most important names and assumptions of posthumanism. However, the painter is mainly interested in the "here and now." This radical life and creative attitude was best interpreted by Karolina Plinta in her text for the "Venom" catalog:

"Czech is a total hardcore," I once heard from a colleague, asking him about the widely discussed paintings, which, by the way, surprised me a bit myself at first. (...) Martina's uncompromisingness and radicalism can, of course, lead to judgments that reek of moralism and even ridicule. Czech, not particularly fond of people (for being evil, for what they have done to her and to the world), is at the same time a staunch defender of animals as defenseless and innocent beings. They are also the more positive heroes of her paintings - they usually appear in her paintings as victims of human stupidity and wickedness, being killed by hunters or cooked on a plate."

Despite all these differences, the early works of Leszek Knaflewski and Martyna Czech seem strangely close to each other, only this affinity is impossible to put into words. Favoring a social life and creative sessions with his colleagues in the Klip Circle, Knaf and Czech, who lived in her own very separate world, had never met. When the painter first saw his drawings she chuckled, "We have nothing in common." And yet.

Curator: Michał Suchora

Fot. B. Górka

The animal motive? The first clue quickly turns out to lead to a dead end. In Knaf's early works there appear, among others, a horse, a cat, swans, but they are only a form, as important (or perhaps as unimportant ) as any other element. Leszek Knaflewski simply did not like animals. He didn't have them as a child, and as an adult he only paid attention to them in his works. The first animal appeared late at the request of his several-year-old daughter. It was a black cat named by her Knafi.

Martyna Czech grew up in a family with agricultural traditions. As a child, she spent a lot of time with her family in the countryside near Tarnow, so from a young age she had contact with farm animals. Importantly, this experience led her to treat them subjectively, rather than as livestock meant to provide their owners with milk, eggs and meat. This empathy was not blunted when she moved out to study, first in Cracow, then in Katowice. All the time the painter endured animals that fell victim to human predation in successive apartments. Animals in her paintings are often their main characters, treated with equal attentiveness to humans.

The differences in the representation of animals can also be seen on a purely formal level. Cats and pigs in Knaflewski's works are only contours, linear outlines, pictograms, graphic representations of some general concept. They are often preparatory sketches for large-scale installations signed "Circle of Clips." In Czech's paintings, the animals, most often her beloved rabbits, always have an individual feature, are more portrait-like, "full". In addition, the titles she gives them ("Subbush of the Crested Rabbit") refer to specific creatures or show a world of complicated emotional relations ("Revenge", "Devotion").

Symbolism? Knaflewski's early drawings and the sculptures and installations created from them are called examples of magic realism by art historians. The random-looking juxtapositions of objects had no rational explanation. These "beautiful as accidental meetings of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table" were the result of the artist's dreams and uncontrolled streams of thought. "Like an ironing board that was burned through with an iron and started surfing like a surfer on a wave," Knaflewski said of his object shown at the fourth exhibition of Circle of Clips at the Great 19 Gallery in 1995.

Any attempts to give them the marks of closed symbolic systems are dismissed by Ewa Moroń (Knaflewski's first wife), who witnessed the creation of the works for 20 years, with a smile. "Why a man with a house instead of a head? Because he does!"

Czech's paintings have a similar mental automatism and a complete lack of calculation. The motif of her painting can be anything: a rabbit, a mood, a word or phrase heard somewhere. Generalizing, Czech paints her immediate environment; the physical one, and the mental one. The artist always gives her works very specific titles, as if she doesn't want to let the viewer arbitrarily interpret her paintings. It's supposed to be this way and that. Sometimes they are brutally direct ("Painting Fowls," "Patch under the Nose"), at other times they are deliberately clumsily poetic ("Born of Paint," "Nostalgia of an Angel"). Anyone can think whatever they like about Knaf's works, Czech leaves no room for interpretation.

Lack of grand narratives? Knaf's drawings, shown at the exhibition, were created during an extremely intense political and social time. The turn of the 1980s and 1990s in Poland was the moment of the final collapse of the People's Republic of Poland and the new order, which was born in pain. This situation was bluntly commented on by the artists of Gruppa, Neue Bieremiennost or Luxus. The Klips Circle, of which Leszek Knaflewski was a member (alongside Mariusz Kruk, Krzysztof Markowski and Wojciech Kujawski), stood by. The draconity of declining communist Poland prompted them not to fight the system, but to build a hermetic, parallel world outside society and politics. They preferred metaphor to manifesto, poetry to politics.

Martyna Czech, in addition to the fact that she "doesn't give a damn about politics," despises attempts to interpret her work through the prism of any philosophical currents. Looking at her works, any solid academic begins to recall in his mind the most important names and assumptions of posthumanism. However, the painter is mainly interested in the "here and now." This radical life and creative attitude was best interpreted by Karolina Plinta in her text for the "Venom" catalog:

"Czech is a total hardcore," I once heard from a colleague, asking him about the widely discussed paintings, which, by the way, surprised me a bit myself at first. (...) Martina's uncompromisingness and radicalism can, of course, lead to judgments that reek of moralism and even ridicule. Czech, not particularly fond of people (for being evil, for what they have done to her and to the world), is at the same time a staunch defender of animals as defenseless and innocent beings. They are also the more positive heroes of her paintings - they usually appear in her paintings as victims of human stupidity and wickedness, being killed by hunters or cooked on a plate."

Despite all these differences, the early works of Leszek Knaflewski and Martyna Czech seem strangely close to each other, only this affinity is impossible to put into words. Favoring a social life and creative sessions with his colleagues in the Klip Circle, Knaf and Czech, who lived in her own very separate world, had never met. When the painter first saw his drawings she chuckled, "We have nothing in common." And yet.

Curator: Michał Suchora

Fot. B. Górka

3.02-4.03.2018, 2018

"Jad 2", BWA Tarnów

Painting exhibition in the artist's hometown

Graphic design: Agata Biskup

Exhibition partner: Bielsko BWA Gallery

Fot. Przemysław Sroka

Graphic design: Agata Biskup

Exhibition partner: Bielsko BWA Gallery

Fot. Przemysław Sroka

7 September- 8 October 2017

Venom, Bielska Gallery BWA

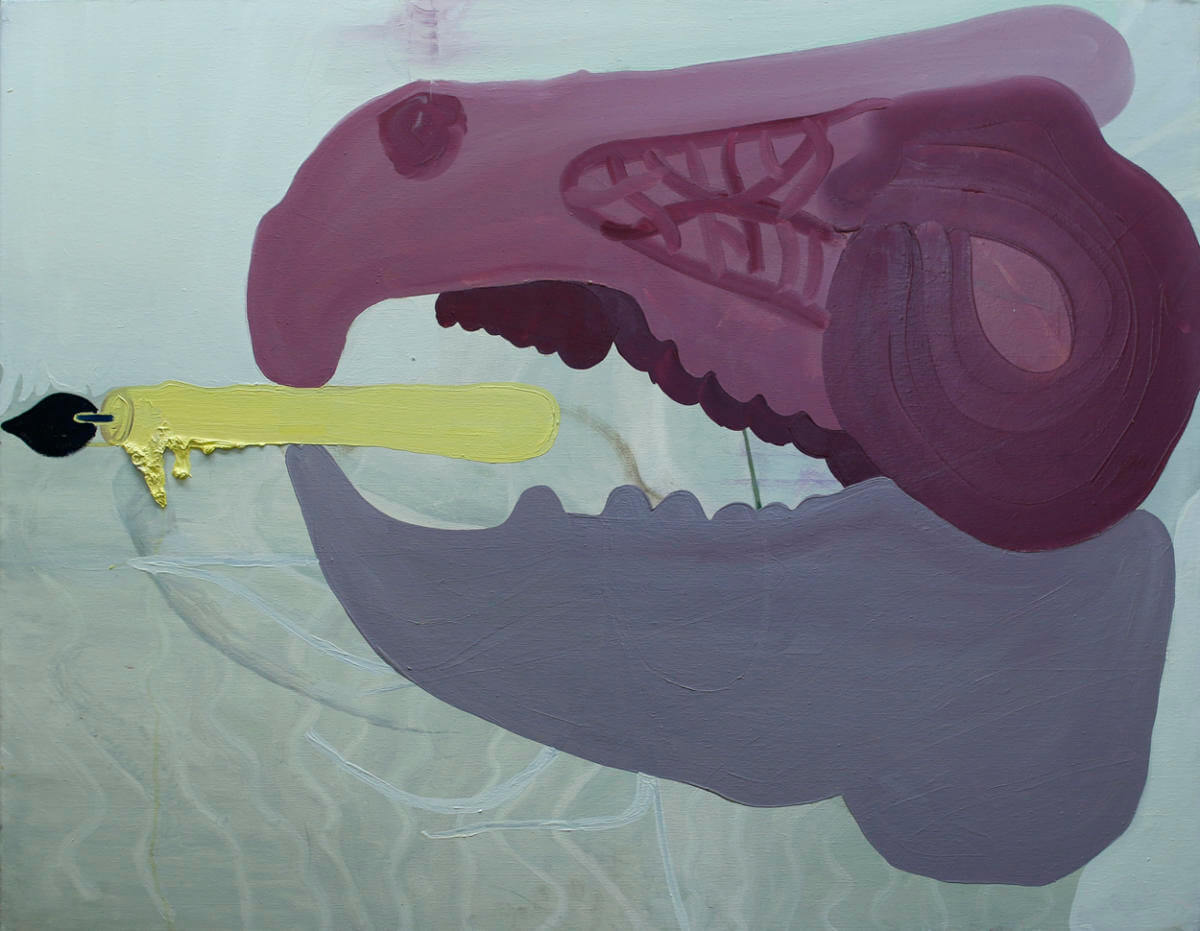

This year's graduate of the Katowice Academy of Fine Arts undergoes a vivisection we haven't had in Polish painting for a long time. Czech paints quickly and greedily, as if her paintings were 1:1 photographs of emotions, without a filter, like quick notes on a napkin in a cafe, like notes in a phone. This is emphasized by the emphatic titles, whose literalness, however, in this case does not offend: Tear, Rejection, Obsession, Temptation, etc.

Czech's painting is thick with paint, and the configurations of the various elements are so peculiar that it often has to take a moment before we realize what we are looking at. And we're looking at basically three motifs: one deals with animal slaughter, another with toxic relationships with loved ones (the most distant?), and a third, perhaps intertwining the others - carnality, sexuality, illness. In Bohemia's case, paint is yet another secretion, and the verisimilitude of the representations even allows one to speak of the abject nature of this painting. This is an affective creation, a painterly cardiogram of emotional stirrings.

The reason for painting a picture in Bohemia is not intellectual speculation or inspiration from any of the university fashions, but experiences, impulses, reflexes. Usually painful, traumatic, deficient. Thus, it is a painterly reflex to the despicable behavior of loved ones; to suffering - one's own and others'; to illness; to misfortune; to unhealed wrongs. Martyn Czech paints the dada."

exhibition curator: Jakub Banasiak

Fot. Krzysztof Morcinek

Czech's painting is thick with paint, and the configurations of the various elements are so peculiar that it often has to take a moment before we realize what we are looking at. And we're looking at basically three motifs: one deals with animal slaughter, another with toxic relationships with loved ones (the most distant?), and a third, perhaps intertwining the others - carnality, sexuality, illness. In Bohemia's case, paint is yet another secretion, and the verisimilitude of the representations even allows one to speak of the abject nature of this painting. This is an affective creation, a painterly cardiogram of emotional stirrings.

The reason for painting a picture in Bohemia is not intellectual speculation or inspiration from any of the university fashions, but experiences, impulses, reflexes. Usually painful, traumatic, deficient. Thus, it is a painterly reflex to the despicable behavior of loved ones; to suffering - one's own and others'; to illness; to misfortune; to unhealed wrongs. Martyn Czech paints the dada."

exhibition curator: Jakub Banasiak

Fot. Krzysztof Morcinek

10.11.2016

CERTAIN CONFLICTS, Potencja, Kraków

Emotional paintings are observations filtered through my mind. The reason for painting is not only a specific event or person-my attitude to the object or subject is also important. The dual outlook is a confrontation between sensitivity to the animal world and hatred of the human world, the result of this collision is a painting/internal pain.

Art is not a form of therapy for me, as I talk about things that cannot be cured (some conflicts can be dragged on endlessly), but with which one can come to terms; just as with the past or the present. Since I was a child, I created a complex system that allowed me to survive, and the systematic ruination of it by human elements brought it to its limits at various stages. Patching the holes was a temporary solution, so fleeting as to be irrelevant.

Text: Martyna Czech

Art is not a form of therapy for me, as I talk about things that cannot be cured (some conflicts can be dragged on endlessly), but with which one can come to terms; just as with the past or the present. Since I was a child, I created a complex system that allowed me to survive, and the systematic ruination of it by human elements brought it to its limits at various stages. Patching the holes was a temporary solution, so fleeting as to be irrelevant.

Text: Martyna Czech